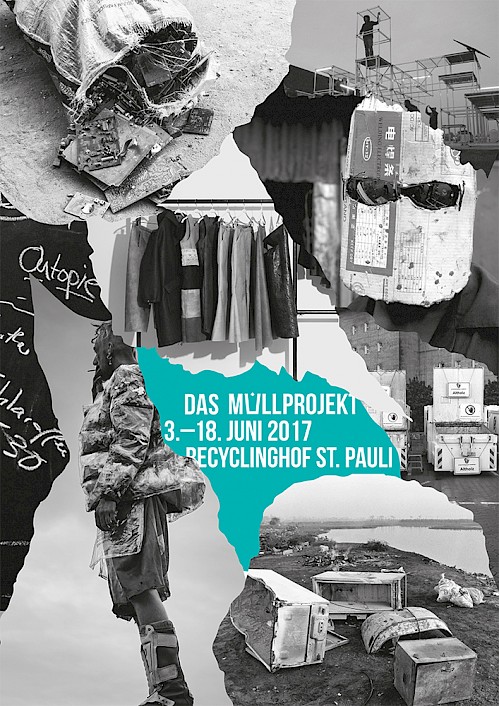

June 2017: the recycling yard in Hamburg, St. Pauli, turns into a stage for 42 hours in the course of 6 days. Waste will be presented and debated in the form of objects, videos, lectures, workshops, artistic interventions, performances, and real junk in containers.

The project was conceived by Nana Petzet (artist), Harald Lemke (philosopher), Anke Haarmann (artist, design theorist) in cooperation with Stadtreinigung Hamburg (municipal waste management). It is a cultural initiative and exhibition platform on the topic of waste involving local players and international guests.

There’s the subway station Feldstraße, the Heiligengeistfeld, the FC St. Pauli stadium, the Rindermarkthalle, the flak tower, a gas station and, right in the midst of it, a recycling yard of Stadtreinigung Hamburg (municipal waste management). Could there be a better place in Hamburg to approach the topic of our current waste culture? From the stage or platform of the recycling yard, the waste issue becomes distinctly perceptible to the senses. Each time something is tossed into one of the containers, private waste turns into a municipal valuable material.

So right here is where the questions arise that we wish to consider: how are the current practices of municipal and commercial waste management to be assessed and where are developments in this field headed? Are life cycles conceivable which lead neither to the destruction of resources nor to processes of downcycling?

The way people deal with waste tells you much about the status of a civilisation, the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan once said. So far, our way of dealing with waste has primarily been based on a strategy of depreciation: with the sentence, “that’s rubbish” something is declared as useless, without value, and is banned from our perception and appreciation. Increasing masses of waste together with declining resources call for new practices in dealing with waste, including an aesthetic revaluation of the invaluable. Emerging beyond the established debate on waste management and life cycle, alternatives such as waste prevention blogs or upcycling trends with a focus on methods of recycling, reuse or revaluation and prevention of waste are gaining in relevance. THE WASTE PROJECT intends to reflect upon this ongoing cultural change with the aid of artistic, philosophical and design approaches. From a critical-creative perspective, it attempts to transform trash into treasures and what is worthless into something precious.

A transformation of waste production will not, however, be achieved merely by means of an enhanced perceptibility through art. It rather requires cultural practices which not only function as aesthetic interventions, but also serve as an encouragement on the practical level. Instead of merely staging waste in an aesthetic manner and creating auratic trash objects, what is needed is “contamination of pure aesthetics” – a disruption of the notion that anything can turn into something beautiful – an intensive examination of issues related to waste on the basis of art, design and philosophy. We wonder: What do we actually perceive as “rubbish”? Can strategies of waste prevention be revalued to develop into future-oriented cultural practices? And how does society handle its waste? Can waste problems be solved on the basis of innovative design? Which philosophical principles would guide such a transformative design?

We suggest the use of “waste” as a kind of renewable resource – continually being produced and replenished all around us and available in huge quantities – and thus to turn a global problem into an “anthropoethical project”. We may assume that the problem of waste is a societal expression or, more precisely, the accumulated societal waste of a collective indifference. In the short era of capitalist industrialisation and the ensuing process of globalisation, the increasing masses of waste – produced in nearly all spheres of life by our modern “disposable society” – were treated as negligible side-effects of progress, all embedded in a consciousness of the benefits of “general wealth”. In this sense, the spirit of our times necessitates a thorough recycling of the definition of human history as a “progress in the consciousness of freedom” (Hegel). Indeed, the ruse of an impure unreason of waste production brings forth the critical insight that the feast may eventually come to its end. Everyday people realise it a bit more clearly: our waste is getting beyond our control and is threatening to make the planet uninhabitable.

The project has its focus on exploring ways to escape the destiny of a total waste pollution. With a series of theoretical lectures, artistic and design-based research and practical showcases, we use waste as a resource for ethical self-reflection and intend to transform it into a sustainable matter for social rethinking. The exhibition, or more precisely, the aesthetic demonstration of imaginable forms of waste management, stages on the premises of a centrally located recycling yard of the municipal waste management. Departing from this special location, we explore various future options and social perspectives of waste minimisation. The topic is being discussed at a place where waste is literally present. Artists and designers work with or against the “trash” and present their visions. Waste experts share their knowledge in dealing with discarded material. Who knows, perhaps our wasting society (Wegwerfgesellschaft) will end up where it actually belongs: on „history's midden heap“ (Karl Marx)—just to transform into a better civilization that does not know anything about waste.

The project is curated by Nana Petzet (artist), Harald Lemke (philosopher), Anke Haarmann (artist, design theorist) in cooperation with Stadtreinigung Hamburg (municipal waste management). It is a cultural initiative and exhibition platform on the topic of waste involving local players and international guests.

For three weekends in June 2017, the recycling yard in Hamburg, St. Pauli turns into a stage for 42 hours on six days, and THE WASTE PROJECT becomes a public exhibition platform. The exhibition is on display during those weekends, and the recycling yard serves both as a stage and showcase. The waste containers of the recycling yard are not closed, but rather fitted with viewing panels allowing insight into the different collecting containers, so that the amount of valuable material is rendered visible. Additional containers are installed for the presentation of the exhibition itself.

The exhibition part of the project feature works from various designers and artists, and include works from the project leaders themselves. Based on the key subjects, guest speakers give lectures related to the theory and practice of “waste management.” The lectures are held in front of a setting of waste. In this context, there are also film screenings. The screenings take place on the grass area behind the containers, as will the Waste Cooking on Saturdays.